If you've spent any time in the church you've read the Creation story. It's dangerously over-familiar so that when we re-read it, we gloss over it or skim. We know how it goes. We know the idea. I'm guilty when it comes to the speedy read through, but tonight at our church small group we found deep truths hidden behind the common words.

Our group is currently working through a curriculum about marriage, and this week focused on the story in Genesis 2:18-24, the creation of Ishah (Heb. - Woman) from Ish (Man). This story is the first account of God naming Creation as being "not good." God creates all the firmament of heaven, the earth has exploded with life, and the Man has just been sculpted from dust and taken on the very Breath or Spirit of God. But not long after we read: "Then the Lord God said, 'It is not good that the man should be alone.'"The following scene tells of Adam naming every creature upon the earth before falling into a deep sleep in his loneliness, unable to find a creature that corresponds to his nature. Yet as he sleeps, God fashions a woman from his rib, taking her from his flesh. And when he wakes, the Hebrew literally reads, "This time, she-is-it! Bone from my bones, flesh from my flesh!"

To understand Creation is to probe the mystery of God's nature. To know the Creation is to know the Creator in some ways. What then can be said that God makes us in need of community? To be alone is not good, so God fashions us within us the desire for the other, the one taken from our flesh or the one from whom we have been taken. The Woman is the only being not fashioned from the earth in the Creation story; instead she is taken from the nature of man. And in that occurrence the nature of humankind develops more fully than before.

When we asked why God would make us with these intense desires for relationship and the need to love and be loved, one of the women in our group said that is the nature of the Trinity. To discover love is to know love with another and the other's love for ourselves. That is why it was "not good" for Adam to be alone; not just because he was lonely. That simply follows from what was already lacking. No, the fact that Creation did not adequately express the mind of God was "not good." Marriage then functions as the sign or sacrament of this grace in the world by joining the two natures to one another as a step towards seeing deeper into the mind of God.

In my own marriage, what I thought was love and the pursuit of mutual felicity changed incredibly when my marriage began to change ME. Our culture only speaks of marriage as one person's individual, independent self being joined to another independent self, and only as long as neither impedes the freedom of the other the marriage is successful. What a horrible view of this gift.

Marriage does not say, 'come as you are and stay that way forever.' Marriage bids you come and love. It is not simply getting your needs met by another, it is the pouring out of our lives to one another while receiving the gift the spouse offers us. And it is worth it because God has fashioned us to 'hold fast' to one another.

The pain and joy and turbulence of this life has required me and my wife to hold fast to one another at times. And I think it may be the mystery of such unconditional love, a love not meant for just happy times but a love meant for the deepest horrors of this life that lets us know Christ's love for his Church. I don't know where I'd be without my wife. It's not always easy, but in the wonder of marriage I have found peace in her gifts to me. And when life and (sometimes) death make it almost impossible to keep going, I know she is my bride, the flesh from my flesh, and that gives me great joy.

To Love, To Hope

Last night a group of high school students from my church discussed Paul's disposition towards death in his letter to the Philippians, particularly in verses 19-30 of the first chapter. This theme of the Christian response to death, or rather how we choose to live in light of its imminence, keeps coming up. Paul, of course, is writing to a church for whom suffering is a present reality. They are oppressed precisely because of their faith, which is an alien experience for most American Christians today. So how then can his attitude be relevant for our churches?

One thing the students noticed is that Paul's attitude is utter foolishness according to the wisdom of our day. Our culture views death as a vague and often distant threat. When it is not being ignored it is being aggrandized to the point of making it unbelievable (think of over-the-top action movies, ridiculously gory blockbusters, or video games that make war entertaining). In this culture, what matters is the now. We are free to further our health, wealth, and felicity given death's non-existence within our worldview. Statements such as, "Christ will be honored in my body, whether by life or by death" are incompatible with our account of the good. We tolerate Christ's commands over our life, but only inasmuch as they cost us as little as possible. This is precisely why, however, when death reenters our narrative through some form of tragedy we find ourselves inadequately prepared to address its ultimate power over us. How can a culture gripped by materialistic impulses to nurture self-worth and self-aggrandizement face a reality that flippantly destroys our highest goods? In short, we cannot.

So what then? How should the church live? One of the students answered this way: "This life doesn't matter." I think that may be going too far in the other direction, but I think it's the natural move. When death comes into the picture, what does matter? Does your job, or your education, or your friends, or your love for anyone really matter? Death doesn't seem to think so. It ravages at will. Sometimes I think the Christian ethic calls us to live in the (sometimes) horrible tension between illusion and despair. Either death is distant so we live engrossed in the present, or death's shadow makes all the world grow dark and all beauty loses its luster. But maybe there is a way to love more then we've ever loved, more deeply than we thought possible, even in the knowledge that death hangs over the best of who we are.

God knows this will cost us in this life. Every time I hear the lyrics to the Mumford and Sons, "After the Storm" this truth hammers home:

And I took you by the hand

And we stood tall,

And remembered our own land,

What we lived for.

And there will come a time, you'll see, with no more tears.

And love will not break your heart, but dismiss your fears.

And we stood tall,

And remembered our own land,

What we lived for.

And there will come a time, you'll see, with no more tears.

And love will not break your heart, but dismiss your fears.

But this hope comes by facing the truth that follows:

I will die alone and be left there.

Well I guess I'll just go home,

Oh God knows where.

Because death is just so full and mine so small.

Well I'm scared of what's behind and what's before.

Well I guess I'll just go home,

Oh God knows where.

Because death is just so full and mine so small.

Well I'm scared of what's behind and what's before.

The song closes with the following lines again:

And there will come a time, you'll see, with no more tears.

And love will not break your heart, but dismiss your fears.

And love will not break your heart, but dismiss your fears.

I hear this type of awareness in Paul. "For to me to live is Christ, and to die is gain." And by this Paul means to gain Christ. N.T. Wright notes in his brief commentary of Philippians that 'heaven' is not the same term for Paul as it is for us. Paul never waxes eloquent on the golden roads or 'mansions,' but he does talk about finding Christ and being found in Christ. For Paul that holds all hope, and for the Church it is our only hope. A Christian ethic then must be enraptured with love, but this love is not threatened or overshadowed by death. It is only made more potent by death, and in dying we find only 'gain,' not loss. In Christ we find Christ's Church, his bride, and in her we find one another. To see my Lord would be to see those whom I love, and those whom I have lost. May we hope to all see that glory, serving one another in love while despising the fading power of death.

Ethics without Death: St. Athanasius on Alabama

What guides our actions? Which impulses, lifestyles, or commandments win out when it comes down to the moments of our decision-making? On the surface, ethics seems such a simple thing. To know the right and to do it. The difficulty sets in when we seek to know what is right, or good.

For Christians, this question is frequently treated as a black-and-white simplicity. Debates ebb and flow over the teaching of Scripture, the ethics of Jesus and so forth with varying groups championing their sources of authority and claiming (with little to no doubt) that their spring of divine wisdom has granted them the knowledge of the good. Knowing this to be the case how do we proceed?

Enter the Immigration Debate. The Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR) estimates thirteen million illegal immigrants lived in the United States in 2007 (http://www.fairus.org/). In 2011 that number has only increased and there has been little improvement towards a helpful resolution. My interest, however, is in the discontinuity demonstrated by the Christian community. Christians, like in so many other issues, disagree on the proper way to respond to illegal immigration. Some argue the law of the land should be upheld, and that all illegal actions are, therefore, immoral or evil by necessity. Others claim self-preservation as their guiding ethic, or more specifically that the existence of cheap labor, free benefits while avoiding certain taxes, or the perceived threat of 'dangerous' foreigners are all reasons to harbor a hostile posture towards illegal immigrants. Still another camp favors a Christological reading of the situation, where we read Jesus challenging us to love even our enemies, to see the despised foreigner as actually our neighbor, and to turn our cheek even after we are struck. This is enough for many of us to throw up our hands and cry it is too complex to resolve. Maybe it is.

But wherever you fall on the politically-charged spectrum of this debate I believe there is something to be learned from St. Athanasius. Not known to many of us Westerners, St. Athanasius was no stranger to debates. In fact, he is chiefly remembered for his own fiery conflict with one of the oldest, strongest, and long lived heresies of the Christian Church: Arianism. And while reading his On the Incarnation with fifteen, first year seminary students at Duke Divinity School, I learned something I had never seen before now. We can either live our lives submitting to the fear and power of death, or we can live with our mind fixed upon the life giving power of the Gospel, a power that does not fear death because it has conquered death. For Athanasius, this truth can be encountered because of one crucial aspect of God's work in the world.

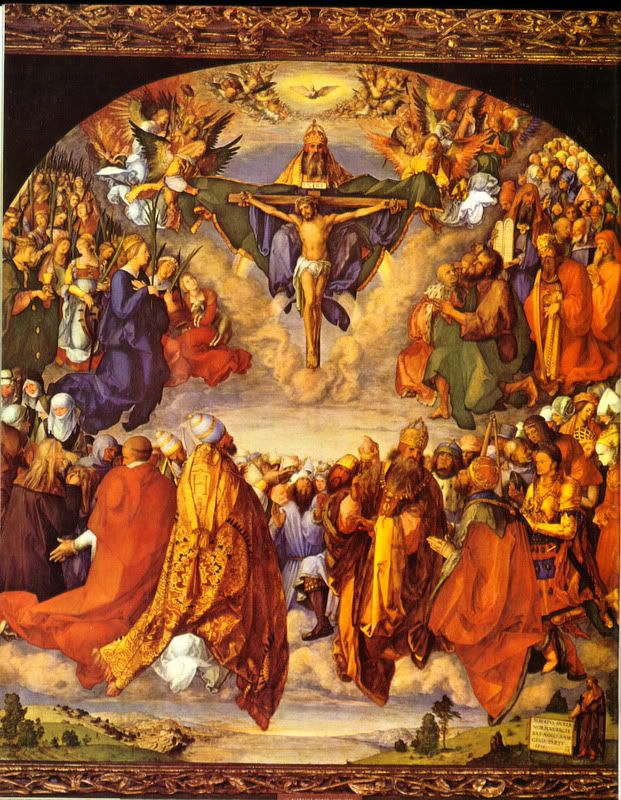

Incarnation. In the beginning God created the cosmos through His Word, and when sin came into the world through the Transgression, humanity lost its innocence and began drifting away from God and eternal goodness and towards the antithesis of good, or evil. So instead of abandoning us to death, Jesus Christ took on the bounds of human nature and flesh and conquered death by dying himself. Then in three days this same Christ rose from the dead, not suffering the power of death to contain his own divine nature, the fulness of life and being. He was the one who gave Life, and that life could not be stilled by death. Because God's Son knew human flesh, human flesh can know God again. And to know God is to know Christ. To know Christ is to know his life, his words, and his actions. All of a sudden Christ's life is extremely important, not just an afterthought to atonement.

And this is why all of this matters for ethics, and in our case, immigration. We are a society absolutely gripped by fear. We are scared or suspicious of everyone and everything. Democrats, Republicans, Muslims, the poor, the rich, politicians, Wall Street, and, of course, immigrants. And we believe this fear gives life. If we fear the right communities or people groups then we can have the proper response to their threat upon our well-being. So, shortly after fear follows hate. And hate can only lead to death.

But then there is Jesus. The ethics of Christ is not one that leads to suburban happiness, wealth, or plenty. But it leads to Life, and this Life has no room for fear, or suspicion, or hate. It is not concerned with death; it is an ethic without death. It loves and only loves. It gives and sacrifices its own self, offering itself up not just for the beloved but also for the enemy. This Love intercedes for the enemy, forgiving the enemy even as the latter murders the former. Our Lord suffered death on a cross, loving his accusers, and forgiving his murderers. And what was their excuse? They were suspicious. They were afraid. So they hated him. And then they killed him.

How then will we choose to live? Can we love enough to have an ethics without death?

[This is on my heart because of the unpopular attention my home state of Alabama has garnered in recent months due to the 'most hostile anti-immigrant law to date.' This article and many of its attached comments offer a good (albeit biased) read on the situation:

For Christians, this question is frequently treated as a black-and-white simplicity. Debates ebb and flow over the teaching of Scripture, the ethics of Jesus and so forth with varying groups championing their sources of authority and claiming (with little to no doubt) that their spring of divine wisdom has granted them the knowledge of the good. Knowing this to be the case how do we proceed?

Enter the Immigration Debate. The Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR) estimates thirteen million illegal immigrants lived in the United States in 2007 (http://www.fairus.org/). In 2011 that number has only increased and there has been little improvement towards a helpful resolution. My interest, however, is in the discontinuity demonstrated by the Christian community. Christians, like in so many other issues, disagree on the proper way to respond to illegal immigration. Some argue the law of the land should be upheld, and that all illegal actions are, therefore, immoral or evil by necessity. Others claim self-preservation as their guiding ethic, or more specifically that the existence of cheap labor, free benefits while avoiding certain taxes, or the perceived threat of 'dangerous' foreigners are all reasons to harbor a hostile posture towards illegal immigrants. Still another camp favors a Christological reading of the situation, where we read Jesus challenging us to love even our enemies, to see the despised foreigner as actually our neighbor, and to turn our cheek even after we are struck. This is enough for many of us to throw up our hands and cry it is too complex to resolve. Maybe it is.

But wherever you fall on the politically-charged spectrum of this debate I believe there is something to be learned from St. Athanasius. Not known to many of us Westerners, St. Athanasius was no stranger to debates. In fact, he is chiefly remembered for his own fiery conflict with one of the oldest, strongest, and long lived heresies of the Christian Church: Arianism. And while reading his On the Incarnation with fifteen, first year seminary students at Duke Divinity School, I learned something I had never seen before now. We can either live our lives submitting to the fear and power of death, or we can live with our mind fixed upon the life giving power of the Gospel, a power that does not fear death because it has conquered death. For Athanasius, this truth can be encountered because of one crucial aspect of God's work in the world.

Incarnation. In the beginning God created the cosmos through His Word, and when sin came into the world through the Transgression, humanity lost its innocence and began drifting away from God and eternal goodness and towards the antithesis of good, or evil. So instead of abandoning us to death, Jesus Christ took on the bounds of human nature and flesh and conquered death by dying himself. Then in three days this same Christ rose from the dead, not suffering the power of death to contain his own divine nature, the fulness of life and being. He was the one who gave Life, and that life could not be stilled by death. Because God's Son knew human flesh, human flesh can know God again. And to know God is to know Christ. To know Christ is to know his life, his words, and his actions. All of a sudden Christ's life is extremely important, not just an afterthought to atonement.

And this is why all of this matters for ethics, and in our case, immigration. We are a society absolutely gripped by fear. We are scared or suspicious of everyone and everything. Democrats, Republicans, Muslims, the poor, the rich, politicians, Wall Street, and, of course, immigrants. And we believe this fear gives life. If we fear the right communities or people groups then we can have the proper response to their threat upon our well-being. So, shortly after fear follows hate. And hate can only lead to death.

But then there is Jesus. The ethics of Christ is not one that leads to suburban happiness, wealth, or plenty. But it leads to Life, and this Life has no room for fear, or suspicion, or hate. It is not concerned with death; it is an ethic without death. It loves and only loves. It gives and sacrifices its own self, offering itself up not just for the beloved but also for the enemy. This Love intercedes for the enemy, forgiving the enemy even as the latter murders the former. Our Lord suffered death on a cross, loving his accusers, and forgiving his murderers. And what was their excuse? They were suspicious. They were afraid. So they hated him. And then they killed him.

How then will we choose to live? Can we love enough to have an ethics without death?

[This is on my heart because of the unpopular attention my home state of Alabama has garnered in recent months due to the 'most hostile anti-immigrant law to date.' This article and many of its attached comments offer a good (albeit biased) read on the situation:

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/04/opinion/alabamas-shame.html?partner=rssnyt&emc=rss ]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)